Warts and All

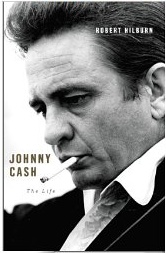

Robert Hilburn’s Johnny Cash: A Life isn’t likely to make many fans among those who adored Walk the Line when it came out a few years ago. Among the many less savory facts Hilburn passes along, you learn that Cash was never able to entirely kick his addictions, going on and off pills until the end of his life. In addition, his marriage to June Carter, usually held out as a model of spousal devotion, wasn’t exactly smooth going for either of them. In fact, more than once they came close to breaking up. And yet Hilburn’s work had the support and participation of both the Cash and Carter clans, and his cover blurbs include a very positive one from Rosanne Cash herself. So what’s up? Why would family members want a book that shows the family patriarch in a less-than-glowing light?

Robert Hilburn’s Johnny Cash: A Life isn’t likely to make many fans among those who adored Walk the Line when it came out a few years ago. Among the many less savory facts Hilburn passes along, you learn that Cash was never able to entirely kick his addictions, going on and off pills until the end of his life. In addition, his marriage to June Carter, usually held out as a model of spousal devotion, wasn’t exactly smooth going for either of them. In fact, more than once they came close to breaking up. And yet Hilburn’s work had the support and participation of both the Cash and Carter clans, and his cover blurbs include a very positive one from Rosanne Cash herself. So what’s up? Why would family members want a book that shows the family patriarch in a less-than-glowing light?

My guess would be because an honest portrait of Cash is more interesting than the usual country hagiography. Hilburn’s affection for Cash is clear—he’s a former music writer for the Los Angeles Times, and he knew Cash from his glory days. Unlike the Hollywood screenwriters who came up with the “feel-good” version of Cash’s life for Walk the Line, Hilburn knows that there are no easy answers to the question of what makes an artist great. There were times when Johnny Cash was a lousy human being, and there were times when he was a transcendent human being, much like the rest of us. And out of this roiling mixture of good and not-so-good, Cash was able to create some spectacular, enduring music.

When I finished Hilburn’s book, I felt drained, but I also felt like I wanted to listen to a lot of Johnny Cash, not just the songs I already had, but the ones I had yet to hear (including the several albums he recorded with Rick Rubin at the end of his life). I had a new appreciation for the complexity of his music and the maelstrom of his life that produced it.

And I think perhaps that’s the problem with our preference for the “feel-good” version of some famous lives. It’s comforting to think that Johnny found June and all his problems were over. We want to believe that other people’s marriages are perfect even though our own demonstrably are not. But that point of view downplays how difficult it is both to be a functioning artist and to have a functioning marriage. I write fiction that emphasizes happy endings, but that doesn’t mean I’m not aware that those endings are a lot more difficult in “real life.”

The thing is, though, Cash’s life does have a “happy” ending, or at least a satisfying one. At the end, his work with Rick Rubin produced some of the best music he’d ever done, and he left Rubin with a treasure trove of songs to be gradually released. Of course, this artistic triumph was accompanied with failing health, financial problems, and the death of the wife he’d come to cherish although he didn’t always treat her well. But that’s the way life is—triumph mixed with disaster, good times and misery.

We fiction writers get to shape our events to our own specifications, but biographers don’t have that luxury. It’s to Hilburn’s credit that even within the tough strictures of reality, he still manages to come up with a treatment that leaves me feeling both exasperation and admiration for Johnny Cash. He was real, and that’s enough.

Posted in Blog • Tags: Johnny Cash, On Life, On Reading, On Writing, Robert Hilburn | 2 Comments

Nice review…I enjoyed it. 🙂

Thanks, Tricia. I don’t read a lot of nonfiction, but this one really appealed to me.